Photography has a historic reputation as a viable mode of archiving history. However, recordkeeping existed long before the advent of the camera and relied on other methods to maintain its existence. For my ancestors, history was kept through oral tradition, dance, and material art. These methods embraced a speculative and communal approach to recordkeeping rooted in personal relationships with the land and one another.

During the Philippines’ American colonial period between 1898 and 1946, American zoologist and photographer Dean Worcester traveled through the Philippine islands and encountered local Indigenous communities who became the subjects of Worcester’s ethnographic photographs. These images became the earliest photographic records of the country’s history, and were published in various government reports and publications. Worcester frequently used his photographs as evidence to support the argument that the Philippines and its people were in urgent need of American intervention for “civilization” efforts. Worcester positioned these photographs as a means to establish himself as an authoritative voice on the Philippines, largely influencing the way Americans perceived the country and helping to justify the country’s colonization. In On Photography, Susan Sontag describes photographing as an act of framing reality and thus an act of exclusion. Despite a modern understanding that photographs are created through the subjective perspective of the photographer, photography maintains a reputation as a tool of objective representation, which has manifested into the dangerous potential for propaganda.

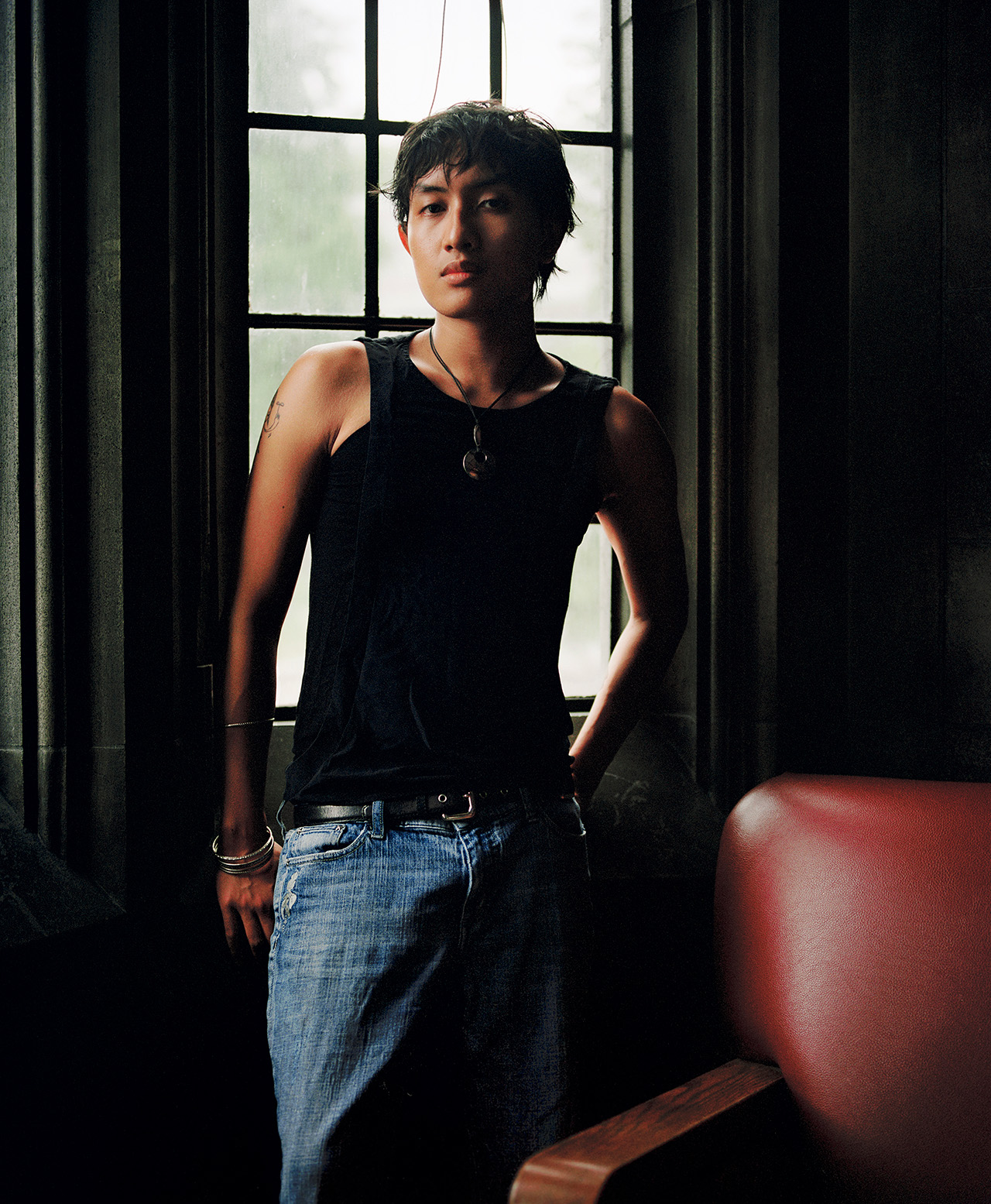

Himala (ᜑᜒᜋᜎ) responds to the colonial legacy of the camera by using folklore and traditions of the homeland to reappropriate the techniques that Worcester used in the photographing of his subjects. These techniques included the use of a large-format camera, which required the photographer to hide under a dark blanket while photographing his subjects, who were often nude and fully exposed. In Himala (ᜑᜒᜋᜎ), the subjects’ faces are intentionally obscured or completely hidden, a deliberate motif to subvert the colonial gaze. This act of concealment becomes an act of protest against the camera’s tradition of surveillance under government bodies. Instead of visible faces, the surrounding imagery and the still-life elements accompanying the portraits take on the role of narrators of the images. Like deities and creatures in Filipino mythology, the subjects’ presences remain to be revealed rather than wholly visible in the viewers’ eyes. Each image is a performance of folklore and traditions that symbolize personal feelings connected to my experience as a diasporic Filipino living in the West, informed by ideas of queerness, religion, placehood, and loss.

Each image is framed as a lightbox reminiscent of the stained glass windows that adorned the churches I grew up in; they are arranged on the ground in the shape of an ancient Filipino symbol known as a Lingling-o, which appeared in the form of amulets that were often worn by Filipino shamans known as babaylan, symbolizing protection from harm and interconnectedness. Inside the circle of photos lies an altar of my own design, made up of banana leaves, ginger, shells, and bones spiralling towards an ashtray and Santo Nino figure at the centre, collectively evoking a space of reverence for the collective histories of the Philippines and its diaspora. Himala (ᜑᜒᜋᜎ) visualizes the multilayered history and culture that permeates the Philippines, representing my Filipino friends and peers in a way that celebrates our multilayered identities and collective experiences.

“An understanding of consciousness need not separate scientific from spiritual, since science simply explains the process that is made profound and personal by spiritual meaning-making.”

— Carl Lorenz Gaston Cervantes, “Philippine parapsychology,” (2024)

Sai Bagni (they/she/he) is a Filipino-Canadian lens-based artist and photographer who lives and works in Tkaronto, Ontario, on the ceded territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples.

Sai’s work responds to notions of images as vessels for truth-telling and history-keeping, analyzing how they inform their own identity formation and relationship to collective existence as a queer Filipino. They are interested in photography as an expression of subjective interpretation rather than an objective document of the world, challenging ideas of representation and memory, and offering alternative ways to engage with the present. Sai has also developed an interest in the photographic object, perceiving materiality as an opportunity to extend an image’s expression and disrupt hegemonic spaces. Their work investigates themes relating to the internet, the queer body, banal environments, the natural world, and collective memory.

They recently exhibited their work at The School of Image Arts for Maximum Exposure 29: Beyond the Surface, and they are currently completing a Bachelors of Fine Arts degree in Photography Media Arts at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Image Arts.